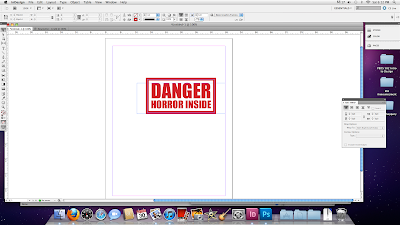

First, use InDesign to create your "stamp." I chose to do this in InDesign because it's more suited for manipulating text and geometric shapes than Photoshop is.

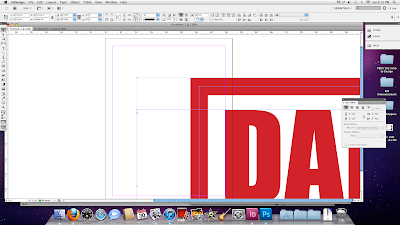

If you're going to use this in a printed project, you'll next have to blow it up really big. I used Transform > Scale at 600%, which ought to be plenty.

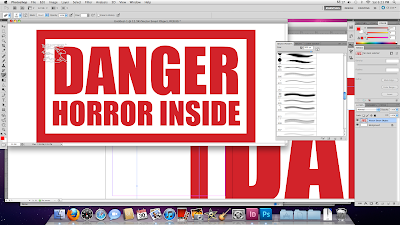

It's huge! Copy it onto the clipboard, launch Photoshop and create a new document. The dimensions of the document should scale automatically to the image on the clipboard, which is exactly what you want. Make sure the resolution is set to 300 dpi, and create your blank Photoshop document. Paste the image in (this creates a new layer, called Vector Smart Object, automatically), double-click it to set it down, and choose the command Layer > Rasterize > Smart Object. This turns the vector image into a form that you can now edit pixel by pixel.

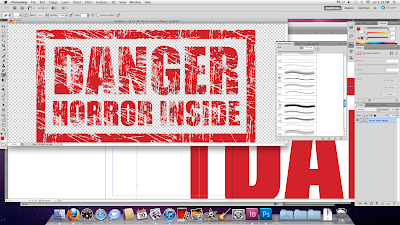

Once that's done, select your eraser tool, make sure it's set to pencil mode (to make nice, crisp scratches) and call up a nice distressed brush. Don't have one? Download some nice ones for free, right here. I used the brushes in this set.

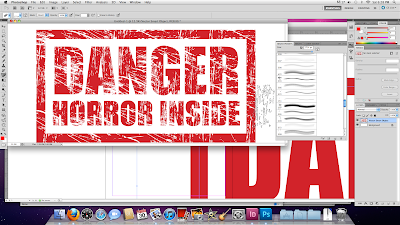

Now go hog wild with the scratch images at your disposal. Don't drag them; just click them once in place. Mix them up, change the sizes and place them all over until you're satisfied.

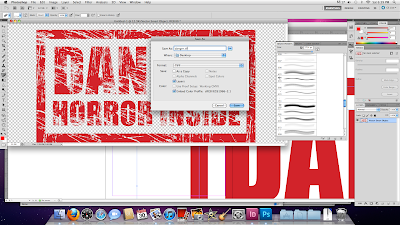

Once you're done, go into the Layers window. You should see two layers: Vector Smart Object, with your illustration, and Background, which is blank. Drag Background to the trash can. This removes the white background and leaves the design transparent.

You're done. Save the illustration as a TIFF file, including transparency.

That's it. You've got a lovely, ugly, high resolution rubber stamp image, ready to place into an InDesign document on any background color or image for all your TOP SECRET, CONFIDENTIAL and FIND HIM AND KILL HIM needs. Enjoy.